I don’t know how many times I heard my father open a conversation with, “Let me ask you a question,” but I know it was A LOT! All five of us understood, when Pop Pop led with those words, we were in for a lengthy discourse on some subject of interest to him, often involving reading material, torn from one of the many publications he received. To this day, my kids will look at me and say, dramatically and with a twinkle in their eyes, “Let me ask you a question.” Then we giggle! For my dad, questions were conversation starters, points of entry, ways to engage with others. He was gregariously chatty, always full to the brim with questions.

Like father, like daughter I suppose, as my teenage sons thought I also asked a lot (too many?) of questions. For instance, if one of their friends was visiting our house and I casually asked, “Tommy, who are you taking to the prom,” I’d get a disgusted eyeroll from at least one of my sons. Apparently, I’d asked a question that was “way too personal” (about who the friend was taking to the biggest public event in high school?) in addition to, for the 36th time (12 per son at least), calling it THE prom instead of its proper Millennial/Gen Z name, prom.

I explained to them my work as a physician required me to ask a lot of questions, I joked it was what I got paid to do. In medical school we learned how to ask questions, sometimes hard ones, and how to keep asking, keep probing, keep reading between the nuanced lines of our patient’s responses. Asking questions is the art of medicine and I loved it! Our instructors taught us, at the end of taking a good patient history (asking A LOT of questions) and doing a thorough physical exam, we should be 95% certain of our patient’s diagnosis. Yes, we could order lab and/or radiology tests or ask for a consultant’s help, but the answer to almost every diagnostic puzzle a patient presented could generally be found in their answers to our carefully crafted questions. I was proud to be a professional question-asker, comfortable wading into exceedingly personal territory, and certain “Who are you taking to THE prom,” did not fall into that category. In my mind I was showing interest in my children’s lives and in their friend’s lives. In their minds I was interrogating. To-may-to. To-mah-to.

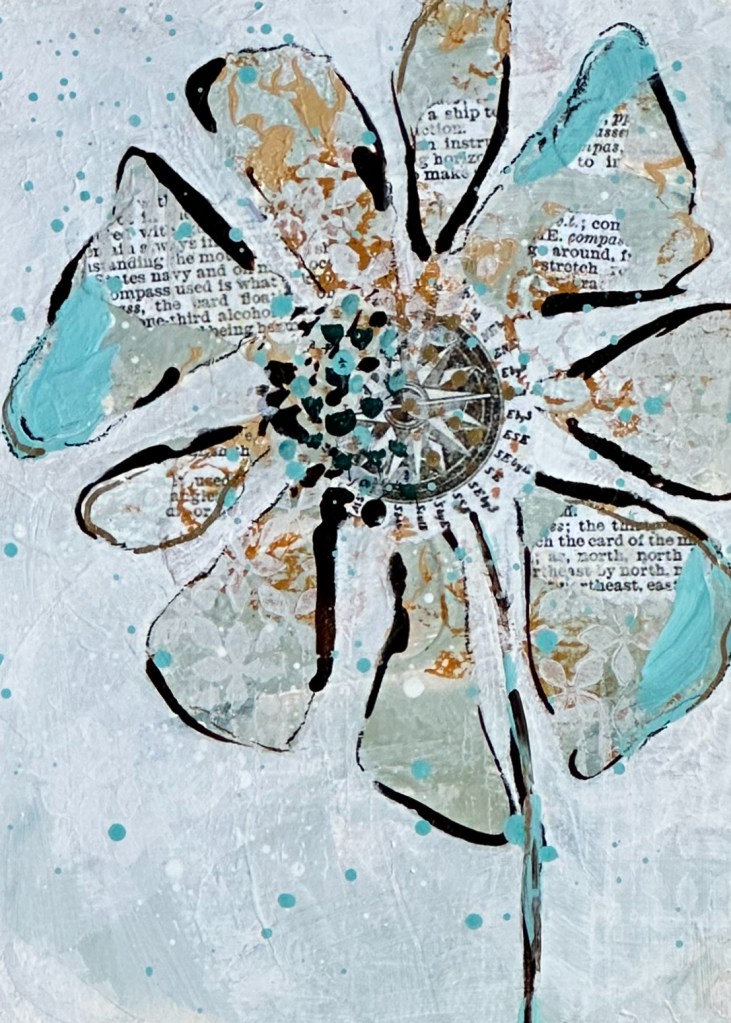

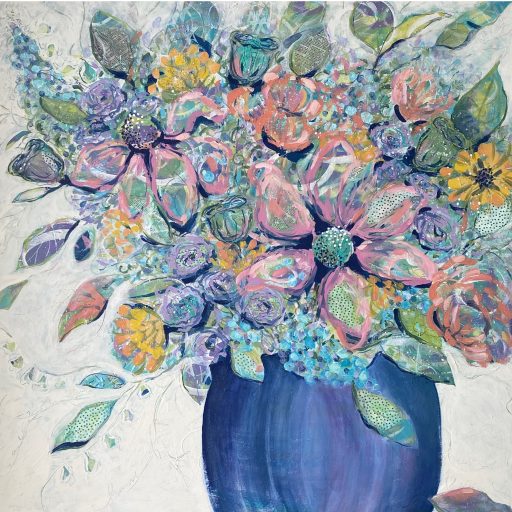

Thankfully for my children, I’ve found a hobby in retirement that stimulates me to continue to ask a lot of questions. This saves them from incessant texts during the day when they may be doing something important, like working. I ask myself things like: what colors of green can I mix from ultramarine blue and cadmium yellow (warm) vs hansa yellow (cool); do I enjoy working in meticulous fine detail or raucous mess-making chaos (this answer surprised my neat, organized, control-coveting self); do I prefer working on paper or canvas or cradled board; am I more comfortable sitting or standing to paint and draw; can I move a project forward in brief spurts (20 minutes) or must I wait for longer expanses of time (1-2 hours) to feel my art making efforts are worthwhile? I could go on and on, the questions in art are unending, sometimes personal, sometimes not.

Every painting I make is a foray into the unknown, a series of questions I’ve asked myself as well as a series of responses I make to questions the art inevitably asks of me. It would be much easier if I found a formula that worked, every time I picked up a brush, that I could simply repeat, but where is the fun in that? Where is the puzzle to solve? Where is the question to answer? Where is the opportunity for my curiosity to inquire, “What happens if?” Every painting, for me, is an opportunity to go on an adventure without a map, without a navigation app, and without directions; an opportunity to ask myself, at every imaginary gas station along the journey, which way should I go? What should I do next? How do I get to my destination? What is my destination?

Unlike the diagnostic puzzles my patients presented over the course of my medical career, when the stakes were high and uncovering the correct answer felt imperative, in art there are a myriad of answers – many possibly right and many, many definitely wrong. Some of my questions lead to discoveries, some lead to dead ends, but all are a necessary part of the process of creating something new. They teach me. They encourage me to keep growing and learning; to keep probing with another, perhaps better, question; to keep playing and experimenting; to keep wasting time; to keep reading between the nuanced lines of my creativity’s responses; to keep solving today’s puzzle and to keep pondering what next step I should take in the studio tomorrow.

In Dr. Seuss’s wonderful book, when the Who’s came out singing on Christmas morning, despite having had all their decorations and gifts and food stolen overnight, the Grinch, listening from atop Mt. Crumpet, was said to have “puzzled until his puzzler was sore.” That’s another line my children and I repeat to each other, and those words fit me to a T. I don’t look to my art for answers, I revel in its questions, in the puzzle of each piece, no matter how complicated it may be, how many steps it may take to “solve,” how many wrong turns it may involve, or how sore it may make my brain. I find joy in the unending questions it asks of me, and I ask of it. There are never too many questions.

Leave a comment